Final Oregon Coastal Coho Federal Recovery Plan Released

Out of all fish in the Northwest currently threatened with extinction, the National Marine Fisheries Service believes Oregon Coast Coho have the best chance at recovery in the next decade per the recent release of the species’ Federal Recovery Plan. Coho salmon, similar to Spotted Owls and Marbled Murrelets, were historically found throughout the Oregon Coast, and are a keystone species whose decline has exposed the tension between the environmental community and extractive industry. The release of the recovery plan is a step in the right direction, but the plan itself won't guarantee improved conditions for Coho.

Coastal Coho in Oregon have been embroiled in legal battles since the early 1990’s. First proposed for listing under the Endangered Species Act in 1995, it took until 1998 for the National Marine Fisheries Service to officially add the fish as threatened. Several lawsuits appealed that decision between 2001 and 2007, including a suit that set the precedent for NOAA’s Hatchery listing policy—a policy that determines whether or not hatchery fish should be included while making listing determinations. Ultimately, Coho salmon retained their status as threatened in 2008, and now, almost a decade later, the Federal Recovery Plan has been released.

The original listing decision emphasized the depressed condition of coastal stocks to be the result of “several longstanding, human-induced factors” (NOAA-NMFS) including over-harvest, artificial propagation, and habitat degradation. When the fish was first listed, fisheries managers focused on the two immediate actions to improve conditions for wild fish: eliminating hatcheries and overhauling how many fish could be harvested through commercial and recreational fisheries.

Hatcheries

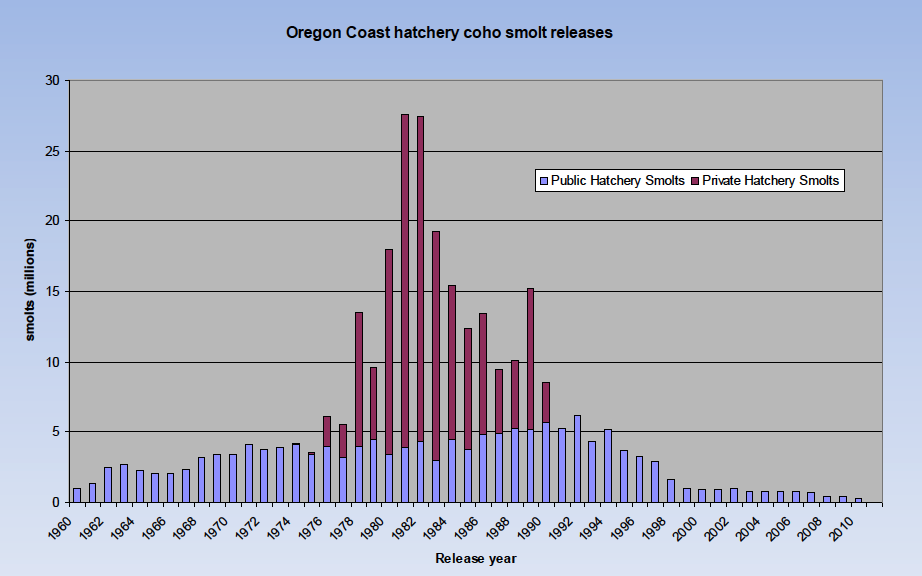

While the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife capped their hatchery production by the mid 1980’s, resource extraction companies were allowed free rein in the “ocean ranching” business up until 1992 to mitigate the damaging environmental impact of their industries. In some years, over 20 million hatchery fish were planted by private entities. Once the fish were listed, in part due to the detrimental impacts of these private hatcheries, there was a 99% reduction in the number of hatchery fish released from peak production in the 1980’s.

Today, just over 102,000 Coho smolts are planted in the North Fork of the Nehalem River and 60,000 smolts are planted in Cow Creek of the South Umpqua Watershed. These hatchery programs combine with approximately 50,000 eyed eggs planted into Depot Bay Creek (approximately 20,000) and the Coos Watershed (approximately 30,000). Currently these hatcheries are under scrutiny by wild fish advocates for differential treatment by NOAA in their recent revisions to hatchery fish protections under the endangered species act.

The good news is that, overall, artificial production has been reduced by 99% since the original listing and Hatchery Genetic Management Plans (HGMPs) have been submitted for all programs being run.

Harvest

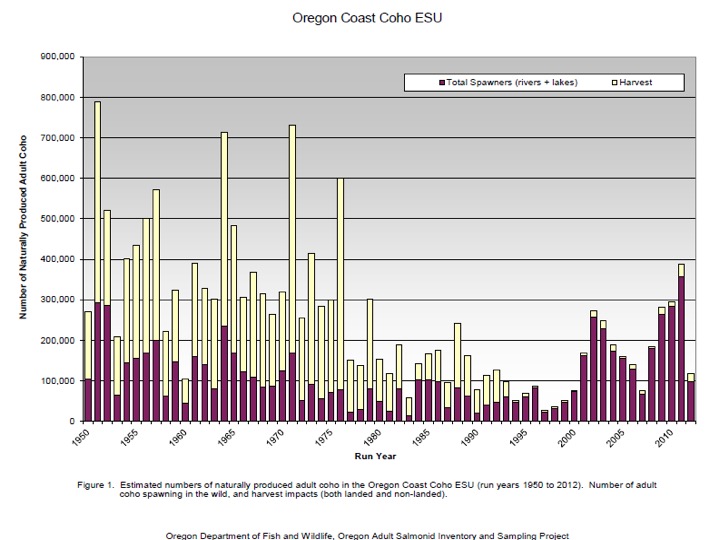

Coho harvest in associated fisheries was also significantly curtailed. In some years leading up to the listing under the Endangered Species Act, 87% of the returning adult salmon were killed in ocean troll and in-river recreational fisheries. Amendment 13, a key element in the Pacific Coast Fishery Management Plan, increased the numbers of fish needed to return to the spawning grounds. NOAA acknowledges that more fish are still needed on the spawning grounds to restore diversity and resilience, and recommend that the Pacific Fishery Management Council take another look at increasing the number of coho returning to the Oregon Coast.

Another positive action taken by NOAA is change in how the fishery has been structured. Once the stock showed signs of rebuilding in the late 2000’s, the National Marine Fisheries Service opened up recreational fishing in independent populations of Coho with a cap on how many fish could be taken from each population. In periods of low ocean-survival, such as in 2016, these fisheries were eliminated in the interest of rebuilding stocks. With total exploitation now between 2-14%, and largely managed on specific population escapement goals, wild Coho are showing signs of recovery.

NOAA notes in the recovery plan “These harvest and hatchery regulations are unlikely to be weakened in the future”.

Habitat

A network of watershed councils was established for community stakeholders to participate in collaborative, consensus-based, habitat restoration projects. Granting agencies such as the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (OWEB) and federal forest stewardship groups have funded over $163 million dollars of habitat restoration on the Oregon Coast since the initial listing.

Even with significant investment, habitat monitoring conducted by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife cannot detect an overall improvement in the quality, quantity, or function of habitat (Anluf- Dunn et al 2014). NOAA, in the Federal Recovery Plan, estimates another $110 million dollars will be needed to restore the habitat necessary for de-listing. While continuing restoration is important to move towards the historic productivity of coastal watersheds, we need to also focus on habitat protection to stop degradation before it begins. Voluntary actions to halt habitat destructions have not been successful since many Oregon Coast streams remain on the 303d list for water quality impairments related to temperature, dissolved oxygen, and sediment. The current status of conducting habitat restoration at replacement value is not a long-term solution to Coho recovery.

Several habitat protection efforts are in the works. Policy makers are reforming the Oregon Forest Practices Act, which would increase stream buffers, the areas around streams off-limits to timber harvest, and add protections to all streams with salmon and steelhead. Floodplain protections have been instated to discourage development in lowland habitats. Still yet to be addressed are agricultural practices and the degradation of estuaries. The Oregon Coast’s productive watersheds are currently capable of supporting hundreds of thousands of Coho salmon returning from the ocean, but with long term investment in habitat restoration and habitat protection measures that prevent us from further degrading watersheds that number could return to an order of magnitude larger.

Oregon Coast Coho and the Native Fish Society

Native Fish Society Staff, District Coordinators, and River Stewards have been working hard to advocate for Oregon Coast Coho since they were listed. Activities have included submitting comments to the recovery planning process, conducting field trips with policy makers, participating in habitat protection campaigns, and working with habitat restoration practitioners.

South Umpqua Steward, Stan Petrowski’s restoration work in the South Umpqua watershed was specifically mentioned in the final version of the Oregon Coast Coho Recovery Plan (Section 6-50). We are thrilled to see his restoration efforts mentioned as an exemplar model for holistic Coho recovery actions. In particular, Stan’s work incorporating beaver as a fundamental component of Coho recovery has proven itself as a model for integrated restoration strategies, and we hope to see more examples of these projects in the future.

It is up to everyone in coastal watersheds, including the local communities, tribal entities, conservation groups, Industry, and Oregon’s political leadership to heed the recommendations made in the Federal Coho Recovery plan.